Review Questions for From a Farmer in Pennsylvania

Frontispiece and title page of a 1903 reprint of the letters | |

| Writer | John Dickinson |

|---|---|

| Country | British Empire |

| Language | English |

| Published | December 1767 – April 1768 |

| Text | Letters from a farmer in Pennsylvania, to the inhabitants of the British Colonies at Wikisource |

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania is a series of essays written by the Pennsylvania lawyer and legislator John Dickinson (1732–1808) and published under the pseudonym "A Farmer" from 1767 to 1768. The twelve letters were widely read and reprinted throughout the 13 Colonies, and were important in uniting the colonists against the Townshend Acts in the run-up to the American Revolution. According to many historians, the impact of the Letters on the colonies was unmatched until the publication of Thomas Paine's Common Sense in 1776.[1] The success of the messages earned Dickinson considerable fame.[2]

The twelve letters are written in the voice of a fictional farmer, who is described as small but learned, an American Cincinnatus, and the text is laid out in a highly organized pattern "along the lines of ancient rhetoric".[three] The letters laid out a clear constitutional argument, that the British Parliament had the authority to regulate colonial trade but not to raise revenue from the colonies. This view became the basis for subsequent colonial opposition to the Townshend Acts,[4] and was influential in the development of colonial thinking about the relationship with Britain.[5] : 215–216 The letters are noted for their mild tone, and urged the colonists to seek redress within the British ramble arrangement.[i] [6] The character of "the farmer", a persona built on English language pastoral writings whose style American writers before Dickinson also adopted, gained a reputation independent of Dickinson, and became a symbol of moral virtue, employed in many subsequent American political writings.[4]

Background [edit]

John Dickinson, the writer.

In the 1760s, the constitutional framework binding Britain and its colonies was poorly defined. Many in U.k. believed that all sovereignty in the British Empire was concentrated in the British Parliament. This view was captured by Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, which stated that "at that place is and must be in all [forms of regime] a supreme, irresistible, absolute, uncontrolled authority, in which the jura summi imperii, or the rights of sovereignty, reside".[v] : 201–202 In practice, however, the colonies and their individual legislatures had historically enjoyed meaning autonomy, especially in taxation.[5] : 202–203 In the aftermath of the British victory over France in the Seven Years' War, in 1763, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland decided to permanently station troops in North America and the Westward Indies. Facing a large national debt and opposition to additional taxes in England, British officials looked to their North American colonies to help finance the upkeep of these troops.[1] : 61–62

The passage of the Postage stamp Human activity of 1765, a tax on diverse printed materials in the colonies, ignited a dispute over the authority of the British Parliament to levy internal taxes on its colonies. The Stamp Act faced opposition from American colonists, who initiated a movement to boycott British goods, from British merchants affected by the boycott, and from some Whig politicians in Parliament—notably William Pitt.[one] : 111–121 In 1766, nether the leadership of a new ministry, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. However, Parliament at the same fourth dimension passed the Declaratory Act, which affirmed its say-so to tax the colonies.[1] : 120–121 In 1767, Parliament imposed import duties—remembered every bit the Townshend Acts—on a range of goods imported past the colonies. These duties reignited the debate over parliamentary authority.[one] : 155–163

John Dickinson, a wealthy Philadelphia lawyer and fellow member of the Pennsylvania associates,[one] took function in the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, and drafted the Declaration of Rights and Grievances.[3] [seven] [8] : 114 In 1767, post-obit the passage of the Townshend Acts, Dickinson set out in his pseudonymous Letters to clarify the constitutional question of Parliament'southward authority to taxation the colonies, and to urge the colonists to take moderate activeness in order to oppose the Townshend Acts. The Letters were first published in the Pennsylvania Chronicle, and then reprinted in nigh newspapers throughout the colonies.[1] [four] The Letters were as well reprinted in London, with a preface written past Benjamin Franklin, and in Paris and Dublin.[1]

The Letters [edit]

The original publication of Letter of the alphabet III, in the 14 December 1767 edition of the Pennsylvania Chronicle. Passages from the letter are visible, alongside a satirical respond by "Ironicus Bombasticus".

Though in reality, Dickinson had little to practise with farming by 1767,[i] the outset letter introduces the author every bit "a farmer settled after a variety of fortunes, nearly the banks of the river Delaware, in the province of Pennsylvania." In social club to explain to the reader how he has acquired "a greater share of knowledge in history, and the laws and constitution of my country, than is generally attained by men of my grade," the author informs the reader that he spends well-nigh of his time in the library of his pocket-size estate.[ix] The author and so turns to a give-and-take of the brewing crisis between the British Parliament and the colonies.

While acknowledging the power of British Parliament in matters concerning the whole British Empire, Dickinson argued that the colonies retained the sovereign right to revenue enhancement themselves. British officials, partially on the advice of Benjamin Franklin,[5] : 212–214, 337 [ten] believed that while American colonists would not accept "internal" taxes levied past Parliament, such as those in the Stamp Act, they would take "external" taxes, such as import duties.[xi] [12] : 34 However, Dickinson argued that any taxes—whether "internal" or "external"—laid upon the colonies past Parliament for the purpose of raising acquirement, rather than regulating merchandise, were unconstitutional.[5] : 215 Dickinson argued that the Townshend Acts, though nominally import duties and therefore "external" taxes, were nevertheless intended to enhance revenue, rather than to regulate trade.

This argument implied that sovereignty in the British Empire was divided, with Parliament's ability limited in certain spheres (such as taxation of the colonies), and with lesser bodies (such equally colonial assemblies) exercising sovereign powers in other spheres. Dickinson further differentiated between the powers of Parliament and the Crown, with the Crown—only non Parliament—having the ability to repeal colonial legislation and to wield executive authority in the colonies.[5] : 216 These views were a significant departure from prevailing British views on sovereignty every bit a central, indivisible power, and they implied that the British Empire did not function as a unitary nation.[v] : 216–217 After the publication of Dickinson'southward Messages, American colonists' views on the constitutional order in the British Empire apace changed, and were marked by an increasing rejection of Parliamentary power over the colonies.[5] : 216–217

Though the taxation burden imposed by the Townshend Acts on the colonies was small, Dickinson argued that the duties were meant to establish the principle that Parliament could tax the colonies. Dickinson argued that in the aftermath of the Postage Act crunch, Parliament was again testing the colonists' disposition.[ane] Dickinson warned that once Parliament's right to levy taxes on the colonies was established and accepted past the colonists, much larger impositions would follow:[5] : 100–101 [1]

Nothing is wanted at habitation just a PRECEDENT, the force of which shall be established by the tacit submission of the colonies [...] If the parliament succeeds in this try, other statutes will impose other duties [...] and thus the Parliament will levy upon us such sums of money as they cull to accept, without any other LIMITATION than their Pleasance.

—Alphabetic character X

More broadly, Dickinson argued that the expense required to comply with any act of Parliament was effectively a tax.[2] Dickinson thus considered the Quartering Act of 1765, which required the colonies to host and supply British troops, to be a tax, to the extent that information technology placed a financial brunt on the colonies.[2] Although he disagreed with the New York assembly'due south decision not to comply with the act, Dickinson viewed non-compliance equally a legitimate right of the assembly, and decried Parliament's punitive society that the assembly deliquesce.[2]

Though he disputed Parliament'south correct to raise revenue from the colonies, Dickinson acknowledged Parliament'south say-so over trade in the Empire, and saw the colonies' interests equally being aligned with those of Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland:[13] : 177–178 [2] : 39 [8] : 115

[T]here is no privilege the colonies merits, which they ought, in duty and prudence, more than earnestly to maintain and defend, than the authorisation of the British parliament to regulate the trade of all her dominions. Without this authorisation, the benefits she enjoys from our commerce, must exist lost to her: The blessings we enjoy from our dependance on her, must be lost to us; her force must decay; her glory vanish; and she cannot endure, without our partaking in her misfortune.

—Letter of the alphabet VI

Beyond the questions of revenue enhancement and regulation of trade, Dickinson did not elaborate a detailed theory of the broader ramble relationship between Britain and the colonies.[viii] : 114–115 However, the messages warned against separation from Great U.k., and predicted tragedy for the colonies, should they become independent:[half-dozen] : 71

Torn from the trunk, to which nosotros are united by religion, freedom, laws, affections, relations, linguistic communication, and commerce, we must bleed at every vein.

—Letter of the alphabet III

In his messages, Dickinson foresaw the possibility of future conflict between the colonies and Uk, but cautioned against the use of violence, except as a last resort:[6] : 71

If at length it becomes undoubted that an inveterate resolution is formed to demolish the liberties of the governed, the English history affords frequent examples of resistance by force. What item circumstances volition in any future case justify such resistance tin never exist ascertained till they happen. Perhaps information technology may be commanded to say generally, that information technology never can be justifiable until the people are fully convinced that any further submission will be destructive to their happiness.

—Letter 3

Instead, Dickinson urged the colonists to seek redress within the British ramble organisation.[6] : 71 In order to secure the repeal of the Townshend duties, Dickinson recommended further petitions, and proposed putting pressure level on Great britain past reducing imports, both through frugality and the buy of local manufactures.[1] [14]

The political philosophy underlying the Letters is often placed in the Whig tradition.[xiii] : 3–45 [4] [14] The messages emphasize several important themes of Whig politics, including the threat that executive power poses to liberty, wariness of standing armies, the inevitability of increasing overreach should a precedent be set, and a conventionalities in the existence of a conspiracy confronting liberty.[4] [14]

Dickinson made use of the common Whig metaphor of "slavery,"[15] which to mid-18th century Americans symbolized a condition of subjection to "the arbitrary will and pleasure of another."[5] : 232–235 The Messages cited speeches given in Parliament by Whig politicians William Pitt and Charles Pratt in opposition to the Postage Act and the Declaratory Act, respectively, describing tax without representation as slavery.[15] [5] Building on Pitt and Pratt, Letter 7 concluded, "We are taxed without our own consent given by ourselves, or our representatives. We are therefore—I speak it with grief—I speak information technology with indignation—nosotros are slaves."[15] [v] Such comparisons led the English Tory writer Samuel Johnson to ask in his 1775 pamphlet, Revenue enhancement no Tyranny, "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?"[16] The contradiction between the use of the slavery metaphor in Whig rhetoric and the existence of chattel slavery in America eventually contributed to the latter coming under increasing claiming during and afterward the revolution.[5] [15]

Literary style [edit]

In contrast to much of the rhetoric of the time, the letters were written in a mild tone.[1] [9] : 126 [3] : 70–71 [xv] : 101–103 Dickinson urged his young man colonists, "Let us behave like dutiful children who take received unmerited blows from a dear parent."[one] In the judgment of historian Robert Middlekauff, Dickinson "informed men'south minds as to the constitutional issues but left their passions unmoved."[ane]

The style of Dickinson'southward Letters is frequently contrasted with that of Paine's Common Sense. In the view of historian Pierre Marambaud, the contrast between "Dickinson'south restrained argumentation with Paine'southward impassioned polemics" reflects the deepening of the conflict between Great britain and the colonies—as well every bit the departure of political views within the colonies—in the years separating the writing of the two works.[3] A. Owen Aldridge compares Dickinson'south style to that of the English essayist Joseph Addison, and Paine's style to that of Jonathan Swift. Aldridge too notes the more than businesslike and less philosophical emphasis of Dickinson's Letters, which are less concerned with bones principles of regime and lodge than Paine'due south Common Sense, and instead focus more than on immediate political concerns.[9] Aldridge compares the character of "the farmer," who contemplates politics, law and history in his countryside library, to the political philosopher Montesquieu.[9]

The classical themes in the Letters—mutual in political writings of the fourth dimension—are frequently commented on.[thirteen] : 48–fifty Dickinson quotes liberally from classical writers, such as Plutarch, Tacitus and Sallust,[nine] : 130 and draws frequent parallels between the situation facing the colonies and classical history. The second letter, for example, compares Carthage'due south employ of import duties on grains in order to extract revenues from Sardinia to United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's use of duties to heighten revenues in its colonies.[7] Each of the twelve letters ends with a Latin epigram intended to capture the fundamental bulletin to the reader, much every bit in Addison's essays in The Spectator.[3] [7] [13] : 49 The final letter concludes with an excerpt from Memmius' spoken language in Sallust's Jugurthine State of war:[7]

Certe ego libertatem, quae mihi a parente meo tradita est, experiar; verum id frustra an ob rem faciam, in vestra manusitum est, quirites.

"For my part, I am resolved strenuously to fence for the liberty delivered downward to me from my ancestors; but whether I shall do this around or not, depends on you, my countrymen."

—Letter of the alphabet XII

The farmer—described as a human being of genteel poverty, indifferent to riches—would have evoked classical allusions familiar to many English and colonial readers of the fourth dimension: Cincinnatus,[2] the husbandman of Virgil'due south Georgics and the Horatian saying, aurea mediocratis (the gilt mean).[3]

Reception [edit]

As French was the linguistic communication of politics in Continental Europe, the French translation published in 1769 (pictured higher up) allowed the Letters to attain a broad European audience.

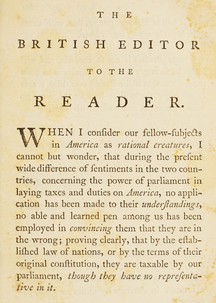

The opening of Benjamin Franklin's preface to the London edition of the Messages, published in June 1768.

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania had a large impact on thinking in the colonies.[1] Between ii December 1767 and 27 January 1768, the messages began to be published in 19 of the 23 English-language newspapers in the colonies, with the last of the letters appearing in February through April 1768.[4] [14] The letters were afterwards published in seven American pamphlet editions.[4] [xiv] The letters were as well republished in Europe – in London, Dublin and Paris.[1] [17] The letters likely reached a larger audience than any previous political writings in the colonies, and were unsurpassed in circulation until the publication of Paine's Common Sense in 1776.[iv] : 326 [xiv]

Prior to the publication of the letters, in that location had been picayune discussion of the Townshend Acts in near of the colonies.[1] Dickinson'south cardinal constitutional theory was that Parliament had the right to regulate trade, only not to raise revenue from the colonies.[4] : 329 Dickinson was not the first to raise the regulation–revenue stardom; he drew on arguments that Daniel Dulany had made during the Stamp Act Crisis in his pop pamphlet, Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies.[12] : 35–36 However, Dickinson expressed the theory more clearly than his predecessors,[5] : 215 and this constitutional interpretation quickly became widespread throughout the colonies, forming the basis for many protests against the Townshend Acts.[4] : 330 Nevertheless, Dickinson's interpretation was not universally accepted. Benjamin Franklin, so living in London, wrote of the practical difficulty of distinguishing between regulation and acquirement-raising,[4] : 333 [2] : 39 and criticized what he chosen the "middle doctrine" of sovereignty.[8] : 116 [18] Writing to his son William, then Purple Governor of New Jersey, Franklin expressed his belief that "Parliament has a power to brand all laws for us, or [...] it has a power to make no laws for united states; and I think the arguments for the latter more numerous and weighty than those for the former".[2] : 39 [18] Thomas Jefferson afterward described the doctrine of partial parliamentary sovereignty over the colonies as "the half-mode house of Dickinson".[four] : 330–331 [19] Franklin nevertheless bundled for the letters to be published in London on 1 June 1768,[20] and informed the English public that Dickinson's views were generally held by Americans.[4] : 333

In March 1768, the town of Boston published a paean to the "farmer" in the Boston Gazette. Dickinson responded in grapheme, signing, "A FARMER".

The broad circulation of the Letters was, in part, due to the efforts of Whig printers and political figures in the colonies. Dickinson sent the messages to James Otis Jr., who had them published in the Boston Gazette, which was affiliated with the Sons of Liberty.[4] : 342–343 Dickinson's connections with political leaders throughout the colonies, including Richard Henry Lee in Virginia and Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina, helped ensure the wide publication of his messages.[4] : 347 Popular pressure was also brought to bear on printers in Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere to print the letters, and to refrain from printing rebuttals.[4] : 343–344

Every bit the messages were published anonymously, Dickinson's identity equally the author was non by and large known until May 1768.[4] : 333 Governor Bernard of Massachusetts speculated privately that the letters might originate from New York.[4] : 333–334 [21] Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of State for the Colonies, might accept suspected Benjamin Franklin of authoring the letters, as Franklin related to his son in a letter: "My Lord H. mentioned the Farmer'south letters to me, said he had read them, that they were well written, and he believed he could guess who was the author, looking in my face at the aforementioned time every bit if he idea it was me. He censured the doctrines as extremely wild, &c."[4] : 333–334 [18] Franklin in turn speculated that a "Mr. Delancey", maybe a reference to Daniel Dulany, might be the author.[4] : 333–334 [18] Due to the initial anonymity of the writer, the character of "the farmer" attained a lasting reputation independent of Dickinson.[4] : 333 "The farmer" was the subject of numerous official tributes throughout the colonies, such equally a paean written past the town of Boston on the proposition of Samuel Adams,[4] : 327 [17] and was sometimes compared to Whig heroes such as William Pitt and John Wilkes.[4] : 327 The letters sparked limited critical reactions in the colonies, such as a series of satirical manufactures organized past the speaker of the Pennsylvania associates, Joseph Galloway, which like the original Messages appeared in the Pennsylvania Chronicle.[4] : 328 The response to the letters was substantially critical in England[4] : 345–346 with but a few favorable views, such equally from Granville Sharp[22] and James Burgh.[23] [24] Tory papers in England rebutted Dickinson'southward constitutional argument by arguing that the colonists were almost represented in Parliament, and by emphasizing the indivisibility of Parliament'south sovereignty in the Empire; these rebuttals were not widely circulated in the colonies.[iv] : 345 Praise for the letters in English language Whig newspapers were more widely reprinted in the colonies, producing a skewed impression in the colonies of the English language reaction.[4] : 328, 345–346

Several colonial governors best-selling the deep impact of the messages on political stance in their colonies. Governor James Wright of Georgia wrote to Lord Hillsborough, Secretary of Land for the Colonies, that "Mr. Farmer I conceive has most plentifully sown his seeds of faction and Sedition to say no worse, and I am lamentable my Lord I have then much reason to say they are scattered in a very fertile soil, and the well known author is adored in America."[4] : 348–349 [14] Dickinson's central constitutional argument well-nigh the distinction between regulation and revenue-raising was adopted by Whigs throughout the colonies, and was influential in the formulation of subsequent protests against the Townshend Acts, such as the Massachusetts Round Alphabetic character, written by James Otis and Samuel Adams in 1768.[4] : 329–330 The development of colonial views was rapid enough that by the mid-1770s, Dickinson's views on the relation betwixt Parliament and the colonies were viewed as conservative, and were even expounded by some Tory leaders in the colonies.[v] : 226 Dickinson's views on sovereignty were adopted by the First Continental Congress in 1774.[five] : 225 In 1778, afterward serious British setbacks in the State of war of Independence, the British regime's Carlisle Committee attempted to reach a reconciliation with the Americans on the basis of a division of sovereignty similar to the i advanced by Dickinson's Messages.[v] : 227 However, by this point, later on the signing of the Announcement of Independence and the drawing up of the Manufactures of Confederation, this compromise position of divided sovereignty within the British Empire was no longer viable.[5] : 227–228

The character of "the farmer" had an enduring legacy, equally a symbol of "American moral virtues."[iv] Subsequent works such as the anti-Federalist pamphlet, the Federal Farmer, Crèvecœur's Letters from an American Farmer and Joseph Galloway's A Chester County Farmer were written in the voice of similar characters.[iv] : 337

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d east f grand h i j thousand 50 m n o p q r due south Middlekauff, Robert (2007) [1982]. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (revised ed.). Oxford University Printing. pp. 160–162. ISBN9780199740925.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Johannesen, Stanley Grand. (1975). "John Dickinson and the American Revolution". Historical Reflections. ii (1): 29–49. JSTOR 41298658.

- ^ a b c d e f Marambaud, Pierre (1977). "Dickinson's 'Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania' as Political Discourse: Ideology, Imagery and Rhetoric". Early on American Literature. 12 (i): 63–72. JSTOR 25070812.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j k 50 m n o p q r due south t u 5 westward x y z aa ab ac ad ae Kaestle, Carl F. (1969). "The Public Reaction to John Dickinson'south 'Farmer's Letters'". Proceedings of the American Antique Gild; Worcester, Mass. 78: 323–359.

- ^ a b c d due east f 1000 h i j one thousand l m north o p q r Bailyn, Bernard (2017) [1967]. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (3rd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Belknap Press of Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-674-97565-1.

- ^ a b c d Ferguson, Robert A. (2006). Reading the Early Democracy (reprinted ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN9780674022362.

- ^ a b c d Gummere, Richard M. (1956). "John Dickinson, the Classical Penman of the Revolution". The Classical Journal. 52 (2): 81–88. JSTOR 3294943.

- ^ a b c d Greene, Jack P. (2011). The Ramble Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-76093-v.

- ^ a b c d eastward Aldridge, A. Owen (1976). "Paine and Dickinson". Early American Literature. 11 (2): 125–138. JSTOR 25070772.

- ^ Labaree, Leonard Westward., ed. (1969). "Examination before the Committee of the Whole of the House of Commons, thirteen Feb 1766". The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 13, January i through December 31, 1766. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 124–162 – via Founders Online, National Archives.

- ^ Forest, Gordon (2011). "The Trouble of Sovereignty". William and Mary Quarterly. 68 (four): 573–577. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.68.four.0573.

- ^ a b Morgan, Edmund South. (2012). The Birth of the Commonwealth, 1763-89 (4th ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN9780226923437.

- ^ a b c d Wood, Gordon S. (1998). The Cosmos of the American Republic, 1776-1787. University of North Carolina Printing. ISBN9780807847237. JSTOR 10.5149/9780807899816_wood.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chaffin, Robert J. (2000). "Chapter 17: The Townshend Acts crisis, 1767-1770". In Greene, Jack P.; Pole, J. R. (eds.). A Companion to the American Revolution. Blackwell Publishers. pp. 134–150. ISBN0-631-21058-X.

- ^ a b c d e Dorsey, Peter A. (2009). Common Bondage: Slavery as Metaphor in Revolutionary America. Academy of Tennessee Printing. pp. 101–103. ISBN9781572336711.

- ^ Hammond, Scott J.; Hardwick, Kevin R.; Lubert, Howard, eds. (2016). The American Debate over Slavery, 1760–1865: An Anthology of Sources. Hackett Publishing. p. xiii. ISBN9781624665370.

- ^ a b Jensen, Merrill (2004) [1968]. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution, 1763-1776 (reprinted ed.). Hackett Publishing. pp. 241–243. ISBN9780872207059.

- ^ a b c d Willcox, William B., ed. (1972). "From Benjamin Franklin to William Franklin, thirteen March 1768". The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 15, January i through December 31, 1768. New Haven and London: Yale Academy Press. pp. 74–78. Retrieved 12 September 2020 – via Founders Online, National Archives.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson: Autobiography, half-dozen Jan.-29 July 1821, 6 January 1821". Founders Online, National Archives . Retrieved 12 September 2020.

What was the political relation between us & England? our other patriots Randolph, the Lees, Nicholas, Pendleton stopped at the half-way business firm of John Dickinson who admitted that England had a right to regulate our commerce, and to lay duties on it for the purposes of regulation, simply not of raising revenue.

- ^ Zimmerman, John J. (1957). "Benjamin Franklin and the Pennsylvania Chronicle". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 81 (4): 362. JSTOR 20089013.

- ^ Nicolson, Colin, ed. (2015). "From Francis Bernard to John Pownall, 9 Jan 1768". The Papers of Francis Bernard, Governor of Colonial Massachusetts, 1760-69, Vol. 4: 1768. Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts. ISBN978-0-9852543-6-0.

- ^ Britain and the American Revolution, by H. T. Dickinson, p. 168

- ^ Neither Kingdom Nor Nation, By Neil Longley York, p. 88

- ^ An English Audition for American Revolutionary Pamphlets

External links [edit]

- Dickinson, John; Halsey, R. T. Haines (Richard Townley Haines) (1903). Letters from a farmer in Pennsylvania, to the inhabitants of the British Colonies. New York, The Outlook company.

-

Messages from a Farmer in Pennsylvania public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Messages from a Farmer in Pennsylvania public domain audiobook at LibriVox

valerioinglacrievor.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letters_from_a_Farmer_in_Pennsylvania

0 Response to "Review Questions for From a Farmer in Pennsylvania"

Post a Comment